As per all sciences, there are general rules, or maxims, which are taken as guidelines when an issue is to be resolved, and genealogy certainly does not lack them. The current maxims of genealogy, especially in the case of Arab-influenced oral lineages, however, mostly deal with similar maxims to that of ‘Ilm al-Hadith, the science of narrations, such as how trustworthy a narrator is, and whether the sources for ones claims is trustworthy or not. Upon the use of Y-DNA sequencing in order to compare these oral lineages (shajra), we have found that the current rules of genealogy don’t always agree with the genetic evidence, leading us to believe that perhaps there are other, more prominent and accurate maxims which can be used in order to examine them, the first of those which I would like to explore here - The maxim of migration.

The general rule of this proposed maxim is simply that migration (prior to the 20th century) skews oral lineage, and therefore

oral lineages are only accurate up to the point of migration

the lesser migration within a family, leads to a more accurate shajra (tree of lineage)

Although there are some minor cases of such skewing happening subsequent to the 20th century, due to how recent it is, and the amount of records more readily available, such flaws in oral lineage are noticeable and can be repaired easily.

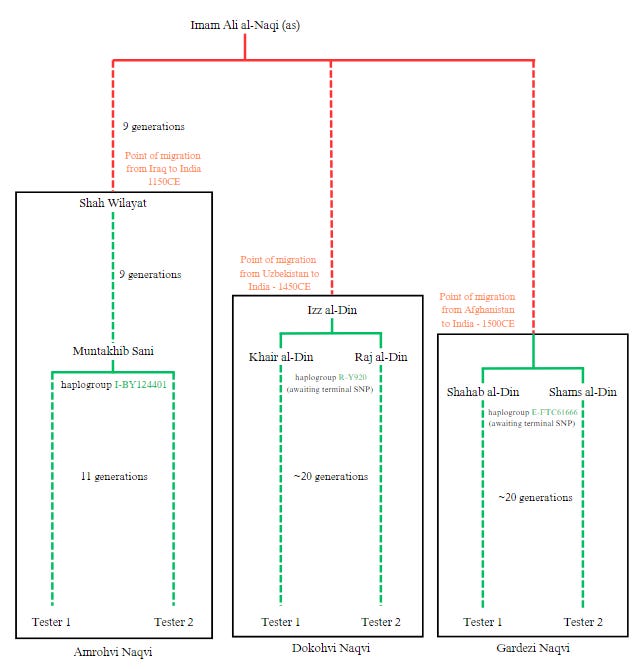

This maxim can be explored by examining the Y-DNA sequencing results of multiple families, beginning with the prominent Sadaat e Amroha. The Amrohvi Naqvi sadaat, who have resided in Amroha since the 13th century, have not migrated since, and therefore, according to the maxim, those Naqvi's in Amroha should share Y-DNA mutations up to the point of migration. This has so far been proven to be true, although based on a relatively small sample size. Two Amrohvi Naqvi sadaat who share an ancestor in 1450CE, share Y-DNA mutations which calculate to an approximate time of 1450CE, showing the great accuracy of both their oral lineages (which held no migration since the late 1200s). This maxim was further proven after testing a claimant from Sadaat e Amroha whose ancestors claimed to have migrated from Amroha to Punjab, likely prior to the 1850s. This man received a completely different haplogroup to those residing in Amroha, showing that migration has indeed skewed his claimed lineage, and he most likely does not descend from the Sadaat e Amroha. Prior to their migration to Amroha, however, the lineage between Imam Ali al-Hadi (as) and Shah Wilayat (the muris a’la of Sadaat e Amroha), also seems to be inaccurate, as those men who have tested do not match anyone from Banu Hashim above their branch from 1450CE, showing that in this case, the maxim is accurate. A similar case of this is seen within the Sadaat e Dakoha and the Sadaat e Gardez. With the Dokohvi’s, their descendants match each other at their muris a’la, Sayyid Khairuddin and Rajuddin Tirmizi, after their migration from Tirmez to Dakoha, but prior to that, their lineage seems flawed, as they do not match who they claim to descend from. The same occurs with the Gardezi’s, as they also match with their muris a’la, but do not match anyone else prior.

Another case of Naqvi’s in which the maxim does not seem to apply are the Bukhari Naqvi’s, of Jalaluddin Surkhposh, and the Bhakkari Naqvi’s, of Sayyid Muhammad Makki. So far, there has been no TMRCA found between any of the descendants of these two families, but rather only mixed haplogroups, which do not match each other. This suggests that the majority of people falsely entered these lineages, as they do not even match at their muris a’la, despite there being little to no migration.

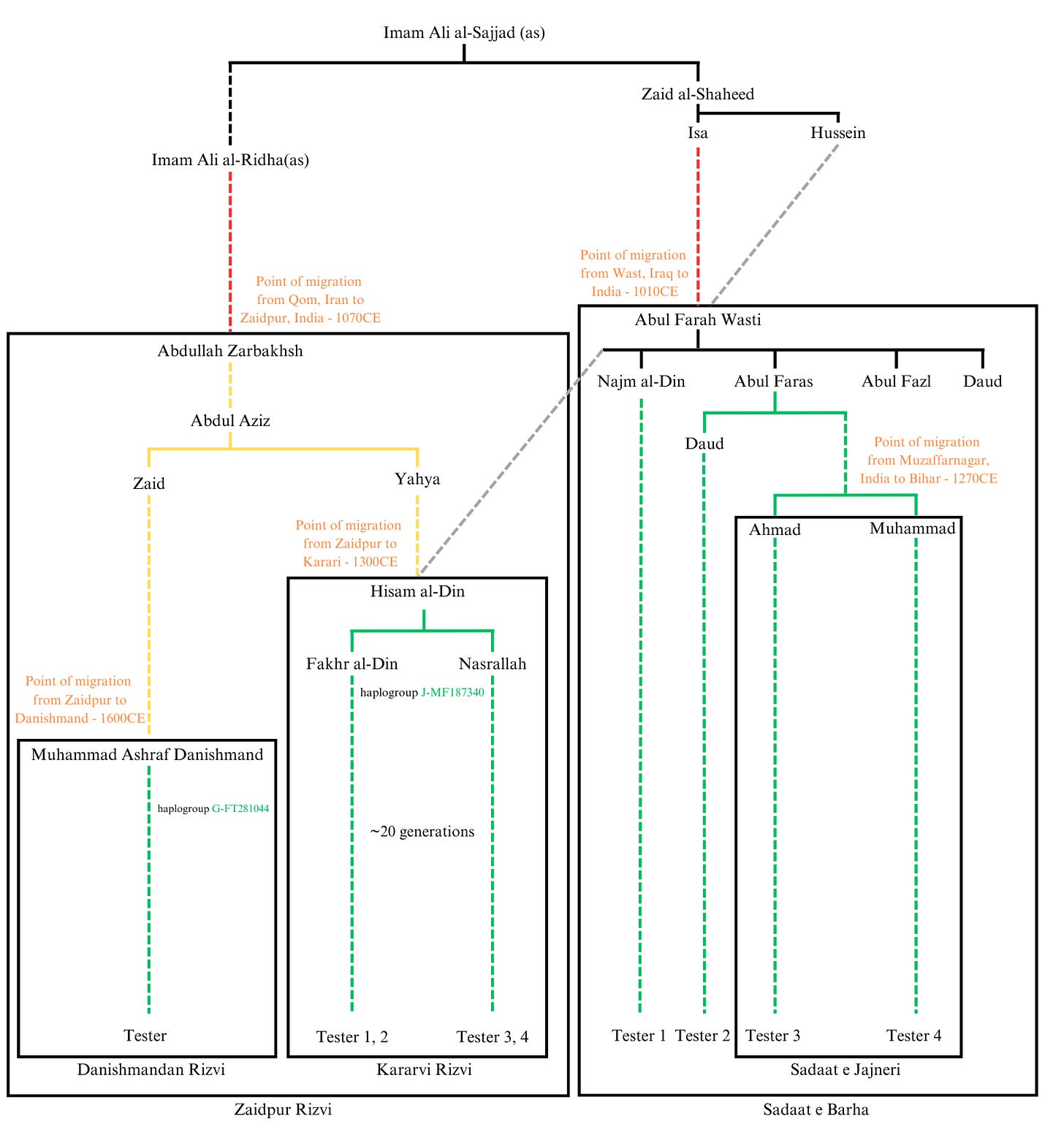

This maxim can be further examined upon the results of two branches of the Zaidpuri Rizvi sadaat. The first being those who migrated from Zaidpur to Karari, around 1350CE. Four different men from different branches of the Kararvi sadaat have tested their Y-DNA, and all match at a TMRCA of approximately 1400CE, showing their lineage has been preserved to their muris a’la, Sayyid Hisamuddin. This branch, however, also brings the first discrepancy, showing the rule of migration to not have fully applied as expected. One of the testers, whose lineage leads to Sayyid Fakhruddin ibn Sayyid Hisamuddin, rather matches the descendants of Sayyid Nasrullah of Sayyid Hisamuddin, leading to some sort of skewing happening within his claimed lineage, despite there being no migration. A second branch of the Zaidpuri sadaat, the Danishmandan, however, agree with the maxim. The Danishmandan descend from a parallel lineage to the Kararvi sadaat, but migrated from Zaidpur to an area near Amroha named Danishmand. Though only one man from their sadaat has tested, he belongs to a different haplogroup, and does not match the Kararvi sadaat, showing that the Danishmandan lineage was also likely skewed due to migration. Further results of different branches of Zaidpuri sadaat, of different levels of migration, will be received in the next few months, allowing for a more accurate conclusion to be made regarding the consistency of our proposed maxim.

Although it is not yet clear if the lineage of the Kararvi sadaat is accurate between their migration from Zaidpur to Karari, it is clear that prior to their lineage in Zaidpur, their lineage in Qom, Iran is not accurate, as rather than matching with descendants of Musa al-Mubarraqa’, as their claimed lineage states, they instead match with descendants of Abul Farah Wasti, a descendant of Zaid al-Shaheed ibn Imam Ali al-Sajjad (as). This again shows the maxim as accurate, and this connection now allows us to explore the Sadaat e Barha, who claim descent from Abul Farah Wasti. If we begin to examine those who claim from Sadaat e Barha, and match with each other, we find that quite a few of them have migrated, leaving the maxim seem inconsistent. Those sadaat who belong to the surrounding villages of Muzaffarnagar all match each other as expected, as there has been little migration, however all those who have migrated, and match with the sadaat in Muzaffarnagar, also all have mention in the verified books of genealogy from Muzaffarnagar. Those who belong to Sadaat e Barha which have migrated and carry a different haplogroup to those in Muzaffarnagar, are not mentioned in the books of Muzaffarnagar, leading to a direct connection between those who truly belong to Sadaat e Barha and the books of Muzaffarnagar.

Some skewing, however, is still present in those Sadaat e Barha who migrated, but still match with their distant relatives in Muzaffarnagar. This can be seen in many of the Jajneri Zaidi sadaat who migrated from Muzaffarnagar to Bihar, who have a distorted shajra between their muris a’la, Sayyid Ahmad/Muhammad Jajneri, and Abul Farah Wasti, which often including random names which do not appear in other books of genealogy, especially those in Muzaffarnagar itself. Not all those who claim from the Jajneri Zaidi sadaat, however, match those in Muzaffarnagar, but since some do, we can rule out migration as the reason of their flawed shajra. Rather, it is more likely it was forged, and they entered into the sadaat near the time of migration of the muris a'la, when the family was not so prominent, and men were easily able to link their lineage to these figures without getting caught. If this theory is true, then it would again show that migration skews shajra, but in a way where men are easily able to falsely enter lineages without getting caught. These theories, however, still require more testing in order to make a more accurate conclusion, as the majority of these ideas are based on relatively small sample sizes.

Upon the topic of entering a lineage falsely, the Tirmizi Zaidi sadaat of Bijnor are prominent, although at first glance, their lineage seems to match the genetic evidence exactly, leaving the maxim not applicable in this case. These Tirmizi Zaidi descendants of Sayyid Hassan Nehtori, however, match one man from Saudi Arabia at a TMRCA of 1650CE. The Tirmizi Zaidi sadaat, which have not had migration since the 12th century, therefore indicating they have an accurate lineage up to that point, lead to the assumption that it is likely the ancestors of the Saudi man reverse migrated from India to Arabia. The Saudi man claims a lineage linking to the Saqqaf branch of the Ba’Alawi sadaat, but he does not match anyone claiming this lineage, therefore showing migration has once again skewed a lineage completely, although it being a backwards migration in this case. There are many cases of families being falsely included in a lineage without migrating, and without being noticed. It is possible, however, that people entered these lineages very soon after migration, as suggested previously with the Jajneri sadaat, and therefore migration still had an impact in the forgeries.

The final case which I shall explore here is that of the Awans, who claim descent from Qutb Shah Awan who migrated to Punjab in the 11th century. Although there are many families who simply did not migrate since, and stayed in that general area of Punjab (the Soon-Sakesar valley), there are two haplogroups present within the Awans residing there: R1a and J2a. The maxim seems to not apply here, however, two theories can be applied. Either that there are two different men which Awans descend from, who lived at a similar time period, or that people simply forged and entered the lineage of Qutb Shah, possibly near to the time of his migration. A more detailed post will be written on them in the coming months, discussing these possibilities, and how the maxim could apply here.

In conclusion, although this proposed maxim applies in many cases, it is still somewhat inconsistent, and more research is required in order to fully portray it as a maxim. Identifying patterns with such lineages with genetic evidence is vital in order to create new maxims which allow us to present ‘Ilm al-Ansab, the science of genealogy, with a brand new face, as we come towards making new discoveries. The more men we recruit to test allow these patterns and theories to be represented as completely accurate conclusions, rather than simple speculations from our current small sample size.